Even though the title of this post refers to “the best films I watched,” I’m including two TV series in here. I don’t really have further commentary on that fact, just an acknowledgment of the discrepancy.

The Comey Rule (developed by Billy Ray, September 2020)

Watching this the week before the election, it was difficult to tell if The Comey Rule was even good. Sometimes I’m in a mood where the artistic merits of a narrative are far less important than my receptivity to the tone or message. I’ve spent the better part of the last five years observing the American political milieu with alternating incredulity and misanthropic scorn, and a project like this is almost laboratory-engineered to activate my confirmation bias. Some of The Comey Rule is really clunky. Poor Jennifer Ehle has to rehearse about half a dozen versions of the wifely wheedle that goes something like, “How can you put your personal ethics above the good of our family?” Ugh. But the cast is generally stellar, and Ray has a real gift for investing scenes of professional bureaucrats making procedural decisions with appropriate dramatic urgency. Of course, the big question mark is Brendan Gleeson as Donald Trump. It’s a remarkable impersonation, maybe a little too low-key. But I lack the perspective to tell if it’s a good performance or a good impersonation or neither or both. Honestly, it just felt a bit weird. I might return to The Comey Rule in a year or two to see if it holds out outside the context of the moment. I can tell you that, having watched it, it didn’t make me feel particularly good about my country or its prospects. Even now, as I write this after the election has been called for Joe Biden, I’m still not feeling particularly rosy.

The Game (David Fincher, 1997)

Entirely by coincidence, I watched this movie on October 11, Nicholas Van Orten’s birthday. There must be something to the season of tricks that lodged this movie in my mind, but I grabbed it by impulse from the shelf at the library and I popped it in during my son’s nap time, and the synchronicity when Michael Douglas corrects Sean Penn about his birthday just hit me in the best weird way. The conceit of a wealthy white dude who looks like Douglas dealing with a midlife crisis by playing an immersive game built around his psychological foibles is not one that holds up super well for me. It’s really a testament to Douglas and Fincher that I find myself invested in this guy at all. Some of the set pieces are also maybe a bit protracted for where the film ultimately ends up, but I still dig how far Fincher leans into the Hitchcock of it all. It’s a film that punishes its protagonist for his own good and revels in it. Great atmosphere, some great set pieces, and just a good, old-fashioned thriller.

Game Night (John Francis Daley, Jonathan Goldstein, 2018)

Of the comedies I’ve seen in the last five or so years, I don’t know how many of them had a first hour as stellar as Game Night. Even if it loses a bit of steam near the end when the stakes compel it to be more of a comedy-thriller, this is what I wish the future of comedy looked like. Just a phenomenal ensemble working from a wickedly funny script guided by visually-assured directors. This is the kind of thing I guess I wish the Russo brothers had cashed in their MCU chips to make, something that people jonesing for more Communityesque projects would lap up. Can’t wait to lob this one at my D&D groups and tell them, “Oh, and the guys who made this are doing the next D&D movie.”

Hocus Pocus (Kenny Ortega, 1993)

Incredibly, I don’t think I’d ever seen this before this October. It’s one of the movies for which people my age have a powerful nostalgia. While I guess I wish I would’ve seen it sooner, I also feel like I never would have fully appreciated just how much heat Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker, and Kathy Najimy are pitching. They’re just incredible. It is so rare to get unambiguously evil villains who are absolutely the heroes in their own quest, only to be foiled by some meddling kids (and a fetchingly beleaguered zombie played by Doug Jones!). There’s a very particular 90s-ness to this movie that makes Hocus Pocus both a time capsule and maybe ripe for a remake. In any case, I will be returning to this one.

The Invisible Man (Leigh Whannell, 2020)

In my previous monthly roundup, I laid down a marker: “if he keeps a steady hand, Leigh Whannell may establish himself as a filmmaker with the stature of John Carpenter in his prime.” That had been my cast of mind having see Insidious 3 and Upgrade within several weeks of each other, but I was also thinking of his Invisible Man when I wrote it. Even with the generally favorable reviews and remarkable worldwide gross, I wonder if this film is going to get its due. Among recent films, only Uncut Gems comes to mind as an apt comparison for how utterly anxiety-inducing Invisible Man is for 3/4 of its runtime. Like Get Out, it also strikes me as a horror film utterly in tune with its cultural moment; the villain is as literal a representation of the male gaze as you can get outside of Powell’s Peeping Tom, a stalker whose camera lenses empower him to surveil and cloak his controlling presence. Pretty much everything here works, from the cast to the production design to the sound to Benjamin Wallfisch’s score. Most importantly, I think, Whannell embraces what his films are—genre flicks—and simply applies his art to packaging the formula in a meaningful, skillfully executed manner. The Wolf Man has never been one of my favorite Universal monsters, but I really cannot wait to see what Whannell does with it. Oh, and Elisabeth Moss? I can’t imagine how absolutely draining this role must have been. She’s amazing.

My Neighbor Totoro [Tonari no Totoro] (Hayao Miyazaki, 1988)

Though I’m not sure I can add much to what has already been said about this marvel of modern animation, I can share an anecdote. This most recent rewatch was the first time that my son sat through the entire film, and watching him watch it was as much a delight as the film itself. Throughout the film, he kept asking where the soot sprites and Totoro were, eagerly anticipating the next encounter with the forest spirits much as do Satsuki and Mei. After the film, though, it wasn’t playing with Totoro that he imagined. Instead, my son, an only child, spent the next twenty minutes trying to find his “sister.” Never underestimate how well Miyazaki taps into the emotional core of his storytelling, and how much that resonates with each generation of viewers.

The Standoff at Sparrow Creek (Henry Dunham, 2018)

I watched this on the first or second of the month, and it unnerved me that only a week later, the FBI announced that they had made arrests in the kidnapping plot against Gretchen Whitmer, governor of Michigan. Austere and ambivalent, I kind of get the comparisons to Reservoir Dogs, but only in the sense that it’s a boiler room chamber drama supercharged with threats of masculine violence. It’s a quiet film with meticulous sound design, lighting, and framing, with a cadre of character actors funneling as much suppressed emotion as they can into thin-on-the-page personalities. Tonally, it feels much more like Bergman directing something that might have gone to Lumet in another era (or, honestly, maybe just straight-up Lumet), but absolutely vibing with the contemporary moment.

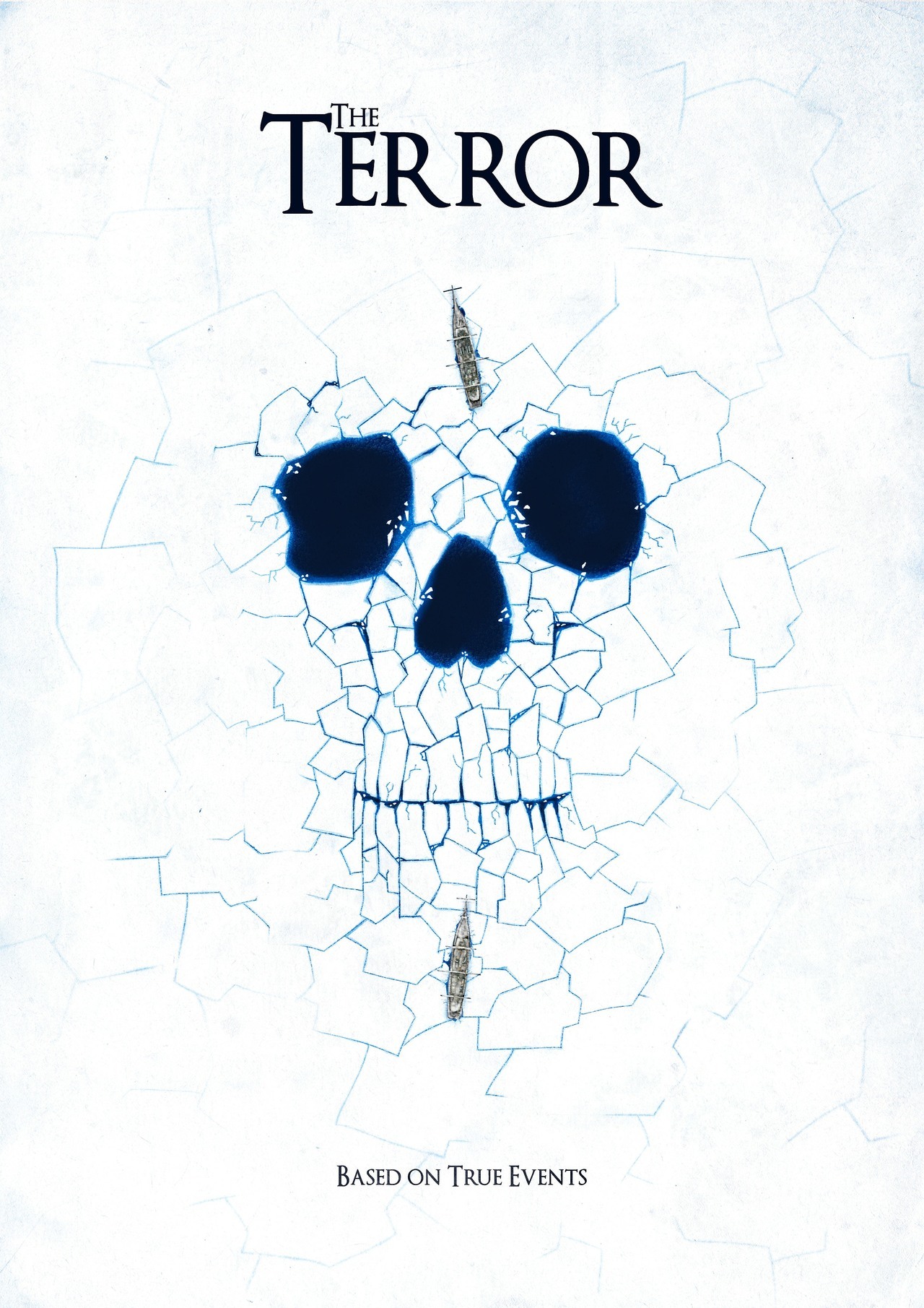

The Terror, Season 1 (developed by David Kajganich, April-May 2018)

Oddly, adding a quasi-supernatural beast to the harrowing true story of two ships’ worth of explorers dying horribly of cold and starvation is maybe the only thing that made it bearable. There’s something about the direct evocation of a horror trope that took this tale of madness and death and translated it into something consumable as entertainment. A filter for the bleakness. This is great television, and it’s an almost paradigmatic argument for television having replaced cinema as the premier purveyor of mid-budget, high-quality ensemble dramas. (And the season is a single, self-contained story, to boot!) It’s a fable about erasure and the terminal limits of of grasping human endeavor. Like most great horror films, it’s bleak without fully embracing nihilism.

Trollhunter [Trolljegeren] (André Øvredal, 2010)

Speaking of nihilism, one of the things I enjoyed and found offputting about Trollhunter is the mordant sensibility. In its best moments, Trollhunter milks dry humor from the workaday mundanity of the titular character’s attitude toward his job. By the end of the film, though, the sheer meaninglessness of his job and the government’s investment in covering up the truth feels simultaneously jokey and archly cynical. Unlike cynical masterpieces like Network or Brazil, though, there’s very little emotional throughline here. It’s all pretty episodic: a series of set pieces showcasing pretty good CG effects (and brilliant sound design) of trolls doing… troll things. Entertaining on the whole, but even with the trollhunter’s arc being pretty well executed, it strains to hold together. In that sense, I guess it’s more true to what you might expect from a feature film spackled together from hours of found footage. Still a bit disappointing, I guess.

Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

This is one of the “wow” viewings of the month. Candidly, I confess that I rather avoided watching this film for years under the assumption that I’d find it a bit impenetrable and downbeat. Turns out, it is both of those things, but it’s also mesmerizing and quite emotionally attuned. For tragedy to work, it has to be tethered to something real and vulnerable. Everything about this film bespeaks tragedy on almost every level, and it works because Glazer is really taking a moonshot here, trying to capture something big about the human experience in a very idiosyncratic and intimate way. Beyond the near-perfection of the shot selections and editing, this feels to me like one of Scarlett Johansson’s deftest moves as a star. Maybe a handful of women in the world could have tackled this material at this point in their career in this decade, and she utterly commits. Besides being a great performance, it’s a career choice that she very obviously did not need to make in order to position herself as a leading actress, but she chose it because it was worthy of someone with her particular charisma and talent and at the right moment for it to shape her star persona. Down the line, this is a fascinating and devastating film made by the right people for the right reasons at the right time. Wow.☕︎