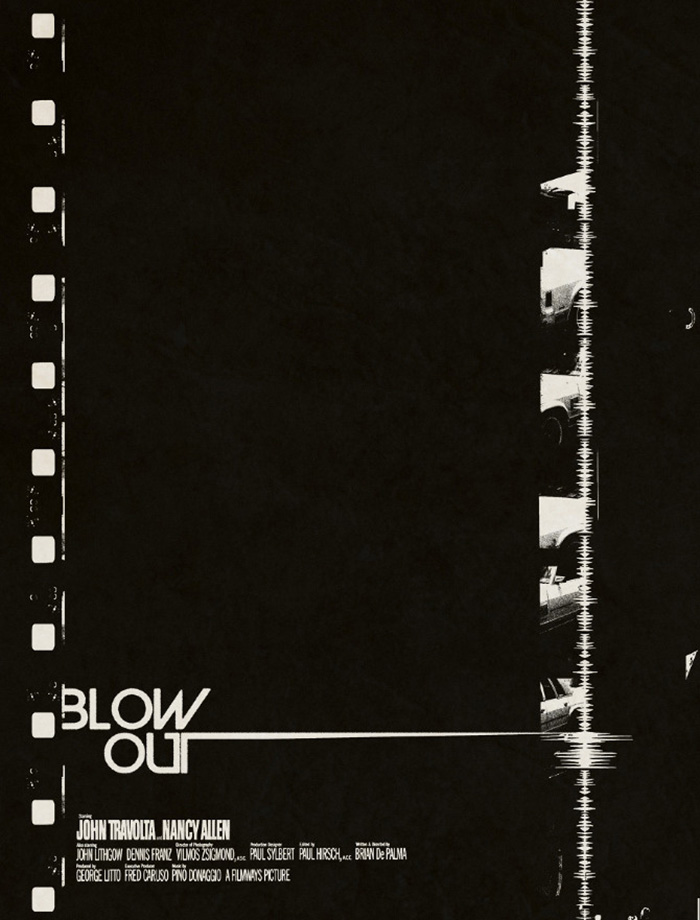

Last August and last March, I rewatched Blow-Up and The Conversation, respectively, and in May I finally finished the trilogy. Of course, it’s not really a “trilogy” in any meaningful sense; at best, it’s a triptych created by viewers and the discourse surrounding these three films whose filmmakers are very obviously intertwined interlocutors. The single biggest pleasure of watching these three films in succession (even if it did take several months) is bearing witness to three filmmakers at the peak of their powers playing variations on the same theme. While The Conversation follows from Blow-Up, Blow Out much more obviously follows from both of them; yet the three films are utterly distinct from each other. What’s more, each is distinctively of its own era’s—and each captures something about each era’s relationship to paranoid politics.

One of the other emergent themes from this triptych is each filmmaker’s comment on the insufficiency of the artist to rise to the demands of his (definitely his, since each film also interrogates masculinity) era. The failures of Thomas, Harry, and Jack to see and hear the machinations happening in front of them and to do anything meaningful with what they uncover is, in De Palma’s film, most bluntly and most sensationally, like a dismembered head bearing witness, stuck on a pike for the audience to contemplate. Like Harry Caul, Jack is destroyed by his prophetic glimpse at the truth. Like Harry, too, Jack is also an expert in his field whose past experiences should have prepared him for his trial.

Unlike Harry, who fruitlessly tears apart his life to thwart the prying eyes and ears directed at him, De Palma has Jack repurpose his failure into a trivial gag—in the service of his art as a film sound technician—that immortalizes it, and it serves in turn as his own private torment. (By the by, I don’t know if I’ve ever been as hollowed out by a John Travolta line delivery as I was in the final scene of this film.) As a valedictory summation of the theme played out by Antonioni and Coppola before him, De Palma simultaneously demonstrates the power of art to respond to the political evils of its time and laughs it off, angrily, as ultimately impotent, as little more than a politically-aware artist make his private self-flagellation into disposable public entertainment.

Any and all of these three films have plenty to say about our own moment, and the refreshing power of each of them indicates to me that we are far overdue for a contemporary master to present his—or her, or their—own variation on this theme.☕︎