Beverly Hills Cop (Martin Brest, 1984)

Wow, is Eddie Murphy amazing in here. Everything in this film is conspicuously constructed around his performance, and I don’t know how many movies achieve the kind of singular status as star vehicles that this one did. It’s also a reminder of how a screenplay often depends on solid structure and the techniques of filmmaking in order to work. The plot is thin; the characters are thin; the beats are familiar. It’s fine. That satisfying rattle and hum you hear when you watch this movie is the mechanics of everything falling into place because the right people came together to make it work. The supporting cast really holds the ground under Murphy’s feet as he struts about like a comedy god; choices in costuming and editing really pop; the music is outer space great. It’s a B movie that scrapped its way onto the A-list, and not all the choices hold up as well (I’m looking at you, odd font choice for the credits sequence, not to mention a few canceled 80s tropes), but overall it does hold up.

Blackhat (Michael Mann, 2015)

All I remembered from when Blackhat came out is that it was received as this huge misfire and flop. Fans of the Rewatchables podcast know that those guys are huge Michael Mann boosters, so when this came up, I was like, “Huh. I’ve seen almost all his other movies. Might as well.” Which is kind of the exact same way I’d recommend it. If you’ve seen all Mann’s other movies, you might as well. It’s too long, and I feel like Chris Hemsworth—much as I love the dude—was miscast. But it’s pretty solid, the kind of espionage action thriller you might associate more with the 70s. What it does most interestingly is shift gears about midway through; at first, you’re watching a cat-and-mouse global caper where a team of good guys tracks a bad guy. Then the last third shifts into revenge thriller mode, and what it really illustrates to me is how terrifyingly unaccountable someone like Hemsworth’s character can be when there are no rules holding him back. In this story, you’re emotionally along for his ride, but then you wonder, “And what is he gonna do now?” Huh.

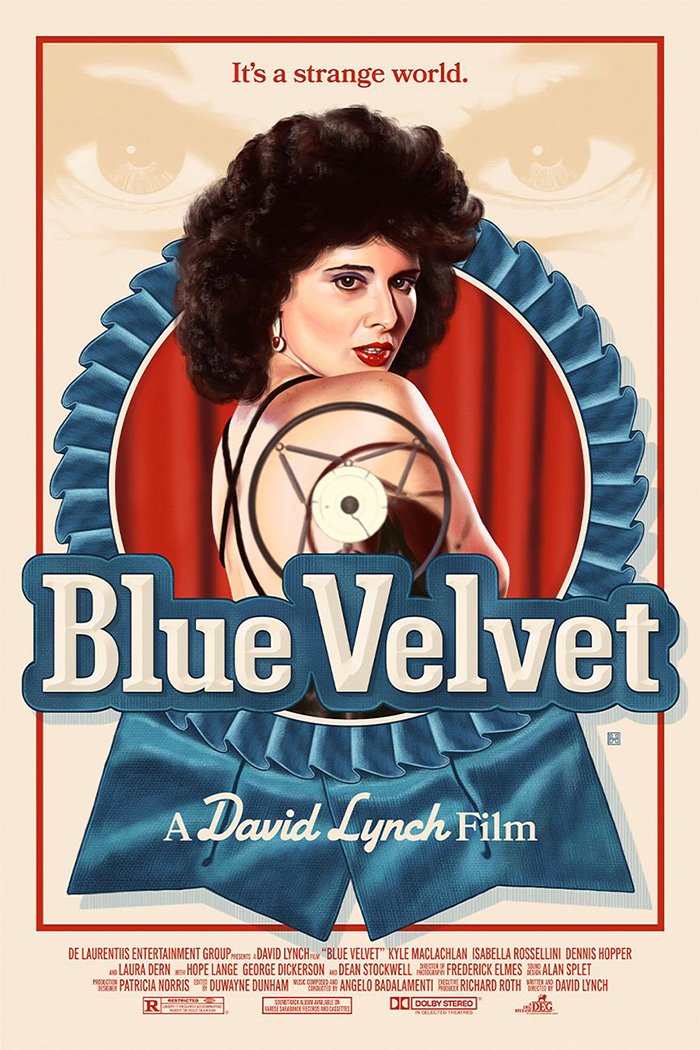

Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

For hopefully obvious reasons, I’ve been thinking a lot about toxic masculinity and white fragility in the last few years, and a lot of the films I’ve chosen to watch pulled me into their orbit because I’d hoped they could interrogate these ideas productively. It’s been way more than a decade since I saw Blue Velvet (maybe two), and it might have been the first proper Lynch movie I ever saw, after Dune. Visually and aurally dazzling, I hadn’t really reckoned before with how assiduously Lynch packs his plot and dialogue with inanity and subversive humor. I can only imagine how thrilling—and/or frustrating—it must have been to be on the front lines of film criticism in 1986, wrestling with whether Blue Velvet was ironic or sincere, profound or silly, and the degree to which conclusions on those issues determined just how well one could tolerate the trials endured by Dorothy Vallens for the sake of the film’s protagonist and antagonist.

Generally speaking, I think it’s boilerplate but true to extol Lynch as a master of his craft. Almost nobody tightropes this dreamlike mode as well as he does; I also think he’s usually most successful when he packages his strangeness accessibly. There’s a reason why you hear more casual cinephiles still love Twin Peaks and Mulholland Dr. but only diehards will puzzle over why you didn’t love Inland Empire as much as they did. At his best, Lynch is simply captivating with his sound and images, and I’m willing to be swept along even if I’m not tracking with how everything fits together.

I wasn’t as satisfied with Blue Velvet this time around. Besides my prudish tendencies, I guess I wasn’t sold on what we’re supposed to do with the duality of Jeffrey and Frank as two sides of the same coin. It may be more honest for Lynch to simply recognize this truth and move on: the happy-clappy ending strikes me as deliberately ironic, a case of negative contrast if I ever saw one, making me doubt the veracity of light and goodness but not providing much else for resolution. At the same time, the point of view of the film is really centered in the privilege of the white male in all his perversity and latent control issues. It feels to me like Lynch is trying to grapple with this and maybe critique it, but I also think that he glides too close to the sun aesthetically; his style is so utterly captivating that we can’t hear or see anything other than what the white male gaze presents (or distorts). So Sandy is a glowing blonde madonna, Dorothy is a mesmerizing fallen whore, etc. Lynch, like Scorsese, is utterly fascinated by the problematic power of this perspective. He saddles the audience with it; it’s totalizing. The fact that it’s so (re)watchable in itself feels a bit wrong to me. Which, I suppose, might be the point. But I’ve always struggled a bit with films that leave the viewer no choice but to be indicted. Is that intentional on Lynch’s part? Or has the benefit of the doubt I’ve extended it gotten way too overextended? Kudos (I guess) to Lynch for making a film complex enough that I don’t think there’s a solution to that problem.

Cooley High (Michael Schultz, 1975)

Kudos to Unspooled for prompting me to watch this. Having watched American Graffiti and Fast Times at Ridgemont High relatively recently, Cooley High strikes me as a livelier, more trenchant variant of the American bildungsroman focused on teen shenanigans. Honestly, it’s just a better film, and more impressive for how much it does with a limited budget. Besides looking great and showcasing an unreal set of performances led by Glynn Turman and Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs, I love that it was set in Chicago. From the opening montage, it was a momentary shock simply to see a skyline other than L.A. or New York. Cooley High makes the most of its locations, production design, lighting, and costumes to sell us on the time, place, and mood. I loved spending time with these characters, I loved the soundtrack, and I was utterly heartbroken by the climax.

Fright Night (Tom Holland, 1985)

On the downside: women are not treated well in this film; not by the film’s perspective. But having rewatched Rear Window just month, it occurred to me that the opening of Fright Night steals shamelessly and productively from the central conceit of forcing you to root for people in a toxic relationship to find their way together because there’s a monster living just across the way. Chris Sarandon is just about the platonic ideal of tall, dark, and handsome; he’s one of the best screen vampires. Fright Night is knowing and earnest about the tropes it employs; its tone feels like a precursor for Buffy the Vampire Slayer in mostly the right ways. Basically, this film was a blast to watch, and I look forward to returning to it.

Gaslight (George Cukor, 1944)

Please see my essay for extended thoughts.

Paranormal Activity (Oren Peli, 2007)

I’d always liked this film, and I think the glut of found-footage horror films from the last decade—not least of which among them are the Paranormal Activity sequels/spinoffs—really obscured what made this one so effective in the first place. The jump scares do not, sadly, work quite as well upon repeat viewing as they do the first time. (And if you’re not one who enjoys the ghost train-style shocks in the first place, I could see this film being an especially tough sit for you.) The strength of Paranormal Activity is actually the toxicity of the relationship at its center.

The deadly mistake of the sequels in terms of narrative vitality was the commitment to an ever-expanding lore soaked in conspiracy and fatalism. Fun though they are, the outcome for each of them is essentially a foregone conclusion, bound by the exigencies of continuity. It’s easy to stop caring or believing in the agency of the characters, because many of them are just going to end up where the filmmakers need them to be in order for them to tie back to the events laid out in the original film.

But in the original film itself, very little of the elaborate backstory is present. There’s simply a woman haunted by a demon who has outrun or overcome its appetite for decades. Until, that is, she moved in with her world-class A-hole of a boyfriend. Without charting the ins-and-outs of their relationship, I can say that it strikes me as one that makes sense, and one that would probably be somewhat workable without the catastrophic external pressure of a supernatural predator.

The genius of Paranormal Activity, as in many stripped-down horror films, is that it gives an externalized form to the emotional and psychological dynamics preying upon the main character. In this case, it’s a boyfriend who gaslights, undermines, and low-key bullies her persistently until she finally gives in to the demon rather than fight with her boyfriend. Katie Featherston and Micah Sloat are really marvelous at playing out the toxic dynamic, and they maintain and unfold the tension between the jump scares. This is a really sharply-observed-and-edited film, and the central tragedy is that—unlike the sequels—Katie does have better options, but commits instead to a deeply unhealthy relationship until it’s too late to stop what’s coming.

Salesman (Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin, 1969)

I can only imagine what it might have been like to watch this movie in a pre-Glengarry world; the patter, the character types, the desperation and swagger are all here, minus the f-bombs. This is one that’s been sticking with me, though, in large part because the directors rather fortuitously happened to land on Bible salesmen. Of all the possible products they could be hawking, Bibles. A number of scenes in the film are chilling, in no small part for the pathos lurking around the edges of the otherwise unsparing, almost austere black and white frames. Everything in the world of this movie feels compromised, and it’s upsetting to see the Holy Bible right in the center of it.

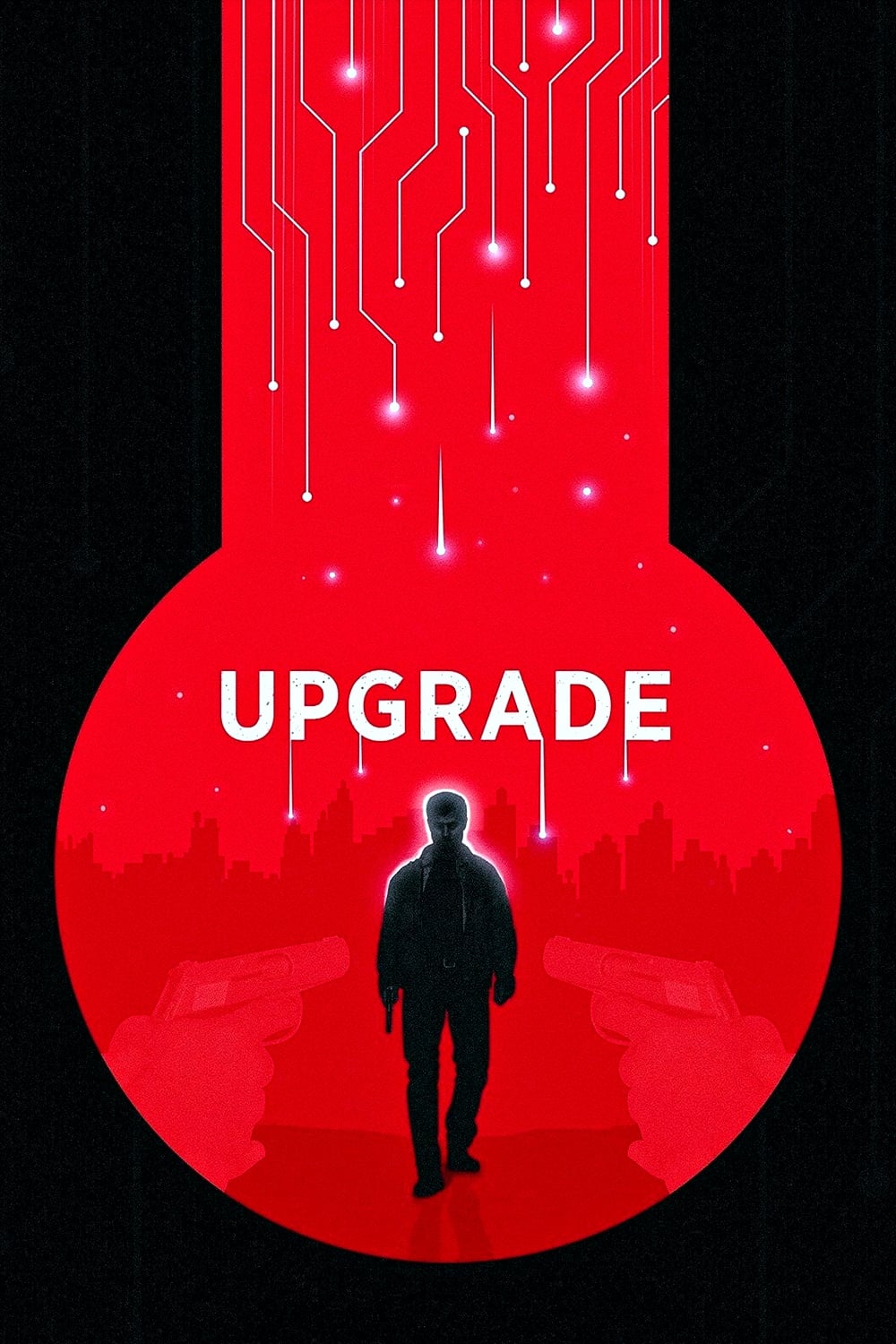

Upgrade (Leigh Whannell, 2018)

Place a marker: if he keeps a steady hand, Leigh Whannell may establish himself as a filmmaker with the stature of John Carpenter in his prime. Upgrade is exactly the kind of exploitation flick with a social point of view that I crave more of, and I’m delighted to be terrified in all right ways by what Whannell delivered. So when you hear Alexa talking to you unbidden, just remember that Upgrade warned you.☕︎

November 9th, 2020 at 7:44 pm

[…] my previous monthly roundup, I laid down a marker: “if he keeps a steady hand, Leigh Whannell may establish himself as a […]